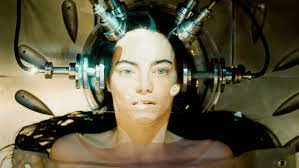

Poor Things is a 2024 film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos and stars Emma Stone as Bella Baxter, Willem Dafoe as her father named Doctor Godwin Baxter, Ramy Youssef as his research assistant, Max, and Mark Ruffalo as her lover, Duncan Wedderburn. Doctor Godwin hires his eager young university student, Max, to come home with him and take on a unique research project. Those of us in academia can recognize the eagerness of Max to move up the intellectual ladder as a protégé and take on the non-IRB approved role as an ethnographer of Bella Baxter, a human subject with the body of a middle-aged woman but the mind of a child that develops and grows as the movie progresses. The film captures the misogyny of the science field in the Victorian era of the 1800s with male scientists dressed in suits and operating on the female subject, even though the film never names a specific era and place. Dr. Godwin Baxter shares his medical files on Bella with Max and explains how he saved a pregnant woman who committed suicide by jumping from a bridge (Victoria Blessington) and replaced the woman’s brain with the brain of the dead fetus in her womb. Deus ex machina is the theme here where men play God with women’s bodies and where Max finds it an honor to meticulously record Bela’s developmental progression.

In an early scene in the film, Bella is depicted as a child learning her first words, wobbling around on the foot of her heels, and captivated by the genetically altered animals wandering around the mansion. There is a homage to psycholinguistic texts such as George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion as well as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as Dr. Baxter and Max map the evolution of Bella. Max is enraptured by his female subject and cannot take his eyes off of her, calling her “stunning”, directing his male gaze at her child-like curiosity as she falls on the ground and makes angels in a mound of leaves and claps her hands like a child with joy and excitement. Max takes out his notebook and starts jotting down what she is observing, acting as an ethnographer and as a child development specialist, as she waddles across the house and gazes at objects of play. When Bella meets Max for the first time though, she punches him on the nose and screams out “Bud”, her father corrects her and says “blood” and after a second try she says “blood” correctly. Children do not learn to master complex phonemes until much later and here you can see how Bella eliminates phonemes and shortens “blood” to “bud”, skipping the initial /bl/ blend sound, reducing it to just /b/ and shortening the complex medial vowel sound. Later, after Max and Bella have developed rapport and Bella trusts Max, she says “outside must go” to Max, speaking in imperatives and engaging in joint attention with Max as he becomes a dyad with Bella. They go outside and experience the greenery of the garden and Bella engages in parallel and solitary play while also throwing temper tantrums. This scene reminds me of the relationship between Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan when the young blind child is described as a colt by the teacher, unrestricted in her movements but whose mind goes on fire when Helen realizes that everything has a name and new words are abstract symbols.

When Bella lays in bed with Dr. Baxter, her surrogate father, while reading a children’s book at night, Dr. Baxter creates a fictious story about how Bella’s parents died and how she is an orphan, an abstract concept for young Bella. She uses prosody with a rising pitch and says “dead” as if she is asking a much larger question: “Are my parents dead?” She also refers to herself in the third person and has yet to develop a sense of self and does not use personal pronouns like “I” and “me” and instead says, “Poor Bella”, to respond to her newfound orphan status. Meanwhile, Max is still walking around with his notebook and pencil and watches and observes Bella play, eat, and wet herself like an infant, knowing that her mental age does not match her chronological age. At one point, Bella is eating kippers and does not like them and makes faces as she tries eating the kippers with her fingers. Max responds with adult language that does not align to her stage of language development and without any motherese, “Do you not like kippers? I am partial to them.” Bella responds by throwing food at him with a mischievous smile.

Soon Bella leaves her childhood behind and begins to explore her sexual urges, rubbing herself against the floor and using objects in the home to provide pleasure. When Max sees this perfectly normal child behavior, he objects in a traditional Victorian manner and represses those urges in Bella and tells her that he does not approve of this behavior and how it is morally wrong. Eventually adolescence comes and Bella engages in sexual masturbation and befriends a stranger who comes to her window, Duncan Wedderburn, a much older man. In the middle of the movie, after she runs away with her lover Duncan to explore the world, there is a scene when they arrive in Portugal and Bella eats pastries for the first time and shoves them in her mouth: “Who made these? We need more.” Her syntax is coming along, depicting the stage of development when children gain a sense of the self and what they desire and want; the speech acts in the film are fascinating as they reflect how Bella organizes her mind. Yet, it is clear that Bella has not yet developed dual representation and does not know how to get inside other people’s minds, alluding to her possibly being on the autism spectrum. After she drives Duncan mad with her childish frankness and endless energy, she pats him on his back in a robotic manner and says, “Are you crying now? What a confounding person you are.” She can display cognitive empathy but not affective empathy toward Duncan; however, this comes toward the end of the film as she matures. In a dinner scene with Duncan and another couple on a double date, Bella is annoyed by the social dynamic and shows her disengagement by frankly stating, “Baby annoying and woman boring.” Bella shows how her lexical categories are mostly nouns and adjectives here and not complex sentences with articles, verbs and prepositional phrases. But she is also showing acts of contestation that are frequent in young children: resistance to or refusal of ideas and positioning. Bella is asserting her identity here and reinterpreting boundaries with Duncan.

By the end of the film, Bella has learned her life lessons, the beauty and evil in the world, and how her sense of agency can only go so far as an individual in a larger society. She can now stand back and use metacognition to observe herself at the micro level as an individual with less status in social structures and hierarchies that disempower women. Yet, there is now heightened self-determination in Bella as she gains macro assertions of freedom at the level of a collective group of women trying to start a feminist movement. As a young woman, Bella shows resistance and agency, as she attunes to the relationships between men and women in the larger socio-political contexts of love and marriage. In the last scene, she is back in the garden with Max, her long lost love, and is reading a book on a recliner chair. Bella is engaged in the everyday act of learning by reading a book, demonstrating what she has accomplished relationally and intellectually through her evolution. Max is no longer her ethnographer and she is no longer his subject and object of study. Bella is no longer a child; rather, she is a woman and has gained that consciousness that Eliza Doolittle does in the film My Fair Lady. Bella is moving to a new space and place, reclaiming herself and reimagining herself in this activity of learning. Bella’s personal act of self-definition emerges from the social histories of women and harks to women today who still confront deficit positionings but who are moving past men when it comes to education levels and leadership roles. Women today are highly engaged, imaginative and confident and are no longer the experiments of men. Poor Things visually depicts personal processes of becoming, and the social and cognitive stages of development in a young child who becomes a woman.